The clerical equivalent of a busman’s holiday in the Bailiwick of Jersey, with the only obligation being the offering of Masses, allows one time to read in the comfortable and hospitably fraternal presybtery at La Cathédrale in St Helier. So while here I have devoured Roger Peyrefitte’s The Knights of Malta, so alarmingly prophetic of the current trials faced by the sovereign order even in the finer details; and Robert Harris’ Conclave (purchased at half price on Jersey, this hardback copy being different to all the others on sale having black-edged pages and a page-marking ribbon) which, despite all the author’s protestations to the contrary, clearly represents some aspects of the modern ecclesiastical reality (and the last twist of which is so absurd as almost to ruin what is otherwise an excellent read; that and his curious translation of the endings of prayers “For Christ our Lord, Amen.” Google Translate?); and just finished minutes ago, Chasing Lost Time: The Life of C.K. Scott Moncrieff, a hardback purchased on sale at Postscript books online.

Scott Moncrieff‘s life (1889–1930) will, in parts, vex the more morally self-sufficient reader. His was a polychrome character: well-adjusted with a wonderful family to whom he was devoted, intelligent and literary but a lover of the military life and the chaotic trauma of the First World War trenches where he was seriously wounded, masculine but homosexual, born Presbyterian but a convert in his youth to Catholicism, adept at secrecy in his life and in his moonlighting for MI6 in Italy. He was arguably the finest translator into English of the last century, and his translations are sometimes considered, as in the case of Proust, superior works to the originals. The book does not labour his sexual life, being far too interested in the man to tabloidize him.

In the current debate about civil divorcees who civilly remarry and yet apparently desire access to Holy Communion without amendment of their lives, Captain Scott Moncrieff stands as a minor but interesting object for reflection. He verged on workaholism, though it were born as often from passion as from industrious dutifulness, and his last years were marked with a two-fold cross of physical affliction: the grave war-wounds to his leg and the unrecognised and slow development of stomach cancer. He diverted large proportions of his earnings to the education of his nieces and nephews and acts of charity to various figures whom he came across. He had a strong sense of honour and loyalty. And he was sexually active; which is to say, homosexually active.

One cannot read man’s soul, especially one dead now for the best part of a century. Yet there are certain indications that merit attention. He was a consistently practising Catholic in the liturgical sense but also in his manner of life, fasting properly for Lent, and living what was for his class and time a ascetic lifestyle, and having no abiding city. He accepted his physical sufferings graciously, only pushing against them in that they kept him from work.

He frequented confession too. Given his many lapses into sexual sin some might be tempted to see in his recurrent moral lapses and sacramental cleansings a possible hypocrisy, and the sort of moral pretense that the early Protestants saw in ex opere operato sacramentalism. His biographer sees in his adoption of Catholicism not some moral casuistry but a real psychological, though she should have added also, spiritual, means for dealing with the deep-rooted condition which so often led him to sin. In the confessional he could safely expose and regret his repeated failure to resist what he knew to be wrong, and hear not harsh words of judgment but words of absolution and encouragement to “go and sin no more”, to which no doubt he sincerely and relievedly clung.

Yet, who among us does not fall repeatedly into the same sins, repeatedly confesses them, repeatedly affirms the desire to avoid the occasion of sin, repeatedly accepts absolution, and then repeats the process again?

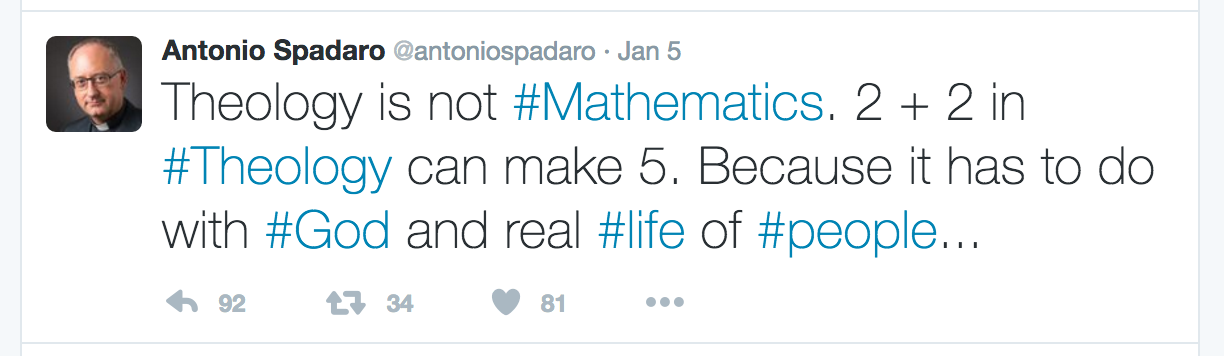

Yet some draw from this fact a conclusion that is markedly at odds with the teaching of Christ, of his Church and of commonsense. Thus the outspoken Jesuit with close access to the pope, Antonio Spodaro:

His Twitter-theology sounds so plausible, which is why it is all the more dangerous. Theology is nothing without scripture, the teaching of Christ, and the reception and elaboration over time of these teachings which we call Tradition. All of those are intimately related to the “real life of people”. Christ dealt with adulterers, prostitutes, extortioners and quislings, among other classes of sinner. He dealt with them mercifully, but his challenge to others not condemn was not a renunciation of God’s right to condemn. It was a warning to us, especially the more religiously inclined, not to take into our hands the prerogatives of God. If we ask, who are we to judge?, we must in all honesty ask also, who are we to acquit?

The word mercy has been much abused in its Tourette-like repetition. It is not free pardon; and it is not indulgence. It is the encounter between human repentance and divine forgiveness. Without repentance the free offer of forgiveness cannot be truly received, and thus there could be no mercy. Christ brought sinners to their senses, forgave them but sent them off always with “Go and sin no more”. In the story of Zacchaeus in Luke 19 this is clearly if lightly pointed out to us:

When he reached the place, Jesus looked up and said to him, “Zacchaeus, come down quickly, for today I must stay at your house.” And he came down quickly and received him with joy. When they all saw this, they began to grumble, saying, “He has gone to stay at the house of a sinner.” But Zacchaeus stood there and said to the Lord, “Behold, half of my possessions, Lord, I shall give to the poor, and if I have extorted anything from anyone I shall repay it four times over.” And Jesus said to him, “Today salvation has come to this house because this man too is a descendant of Abraham. For the Son of Man has come to seek and to save what was lost.”

Zacchaeus encounters the Lord, repents and changes his life, commits to restitution rather than seeking the indulgence of a “clean slate”, and in this encounter recognises an icon of what he has come to do—”today salvation has come to this house”. This is real life and real sin and real mercy. No room for Christ in that sort of self-serving, patronising nonsense that can say with a straight face that in “theology” 2 plus 2 can equal 5 because it deals with real life. Such theology is not grounded in Christian reality but has become an exercise in academic pseudo-theology divorced from the real life of the Church and of people.

Scott Moncrieff did not want the Church to redefine his sin out of existence in an exercise akin to decreeing that 2+2=5, or that black is white, or that water is dry. He did not seek sophistry from the Church so that he might not be confronted with the reality of his sin. The elephant would have remained in the room. His sin would have remained even if some misguided prelate or confessor decreed that homosexual acts were not against Christian teaching. Such a decree would have been of the same order as King Canute ordering back the tide. The tide still came in; sin would still remain.

What Scott Moncrieff sought and found in the Church was meaning in his endless struggle against sin, and the means to renew his part in the struggle. He sought not escape from reality but empowerment to face it. While he failed more than once, and had to seek to authenticate his repentance in confession each time, he nevertheless maintained a lifestyle that authenticated his purpose of amendment: generosity and responsibility towards family and friends, sobriety of life, worthy work for the good of humankind. His physical sufferings graciously and grace–fully accepted became for him a penitential mode of life by which he was able to demonstrate to the Lord the same spirit of real repentance that led Zacchaeus to recompense those whom he had wronged.

Scott Moncrieff wronged God above all, and his fruitful acceptance of physical suffering allowed him to share in the Cross of Christ, which is the only all-effective recompense human flesh can make to God.

Sin endures despite the well-intentioned fantasies of some clergy and theologians. Repent remains the first word of the gospel, and so also its last. Forgiveness is the guaranteed response from God to repentance. Only in this exchange do we truly see mercy. The rest is at best bumf; at worst, a snare to sinners, not a help.

A man may tell me that for a thousand reasons I have not really sinned, and yet my heart will still be unsettled. What brings peace to my heart in confession is not a man’s “You have not sinned as far as I am concerned”, but God’s “Your sin is forgiven; go and sin no more”.

such good stuff here Father—and then we throw in all that hashtag business…tweets and twitter—I prefer the meat and potatoes of the words and the story—and in the end…that of the Salvation being offered to us all—no hashtags coming from Heaven thankfully 🙂

happy retreating Father 🙂

There might be a few hashtags from heaven. #repent ?

HaHaHa 😇

Thank you for another thoughtful and timely post, Father. The word “mercy” is put about so much, and it is always good to be reminded that mercy follows from repentance. I often wonder if the word “compassion” might not be better (and more accurately, in many cases) used than “mercy”. Perhaps you will write a learned post for us on this concept, Father.

Ah, my friend, I have only a small amount of “learned” within me! But I take your point. Compassion is a rich concept – to suffer with.

I realize your post does not have a literary intention, Father, and I agree entirely on your main point about the essential and unavoidable nature of Confession: but just by the way, I looked up CK S M and found a considerable body of work quite apart from Proust’s ‘A la Recherche’ – as if that would not have been enough for one lifetime. But it wasn’t a lifetime at all. Into just *twelve* (12!) brief years of literary activity before his premature death at the age of 40, and while suffering the ill-health you describe, he managed to pack in: a verse translation of Beowulf and several other Anglo-Saxon poems, several works by Stendhal, including the voluminous novel ‘La Chartreuse de Parme’, the Letters of Abelard and Heloise, plays by Pirandello, the Song of Roland, the latin Satyricon of Petronius; and a Pirandello-tinged satire against the Sitwells. (I nearly forgot to mention his many reviews for Chesterton’s ‘New Review’, and another epic novel by a now-forgotten French writer, ‘…& Co’ by Jean-Richard Bloch.)

Faced with such determined and concentrated creative activity, one can feel only awed, daunted and ashamed. (I said a ‘Requiem aeternam’ for the repose of his soul.)

You should get the biography, vastly reduced at Postscript books. It’s an engaging read and he comes out a likeable man, his moral flaws notwithstanding. But who am I to judge? 😉