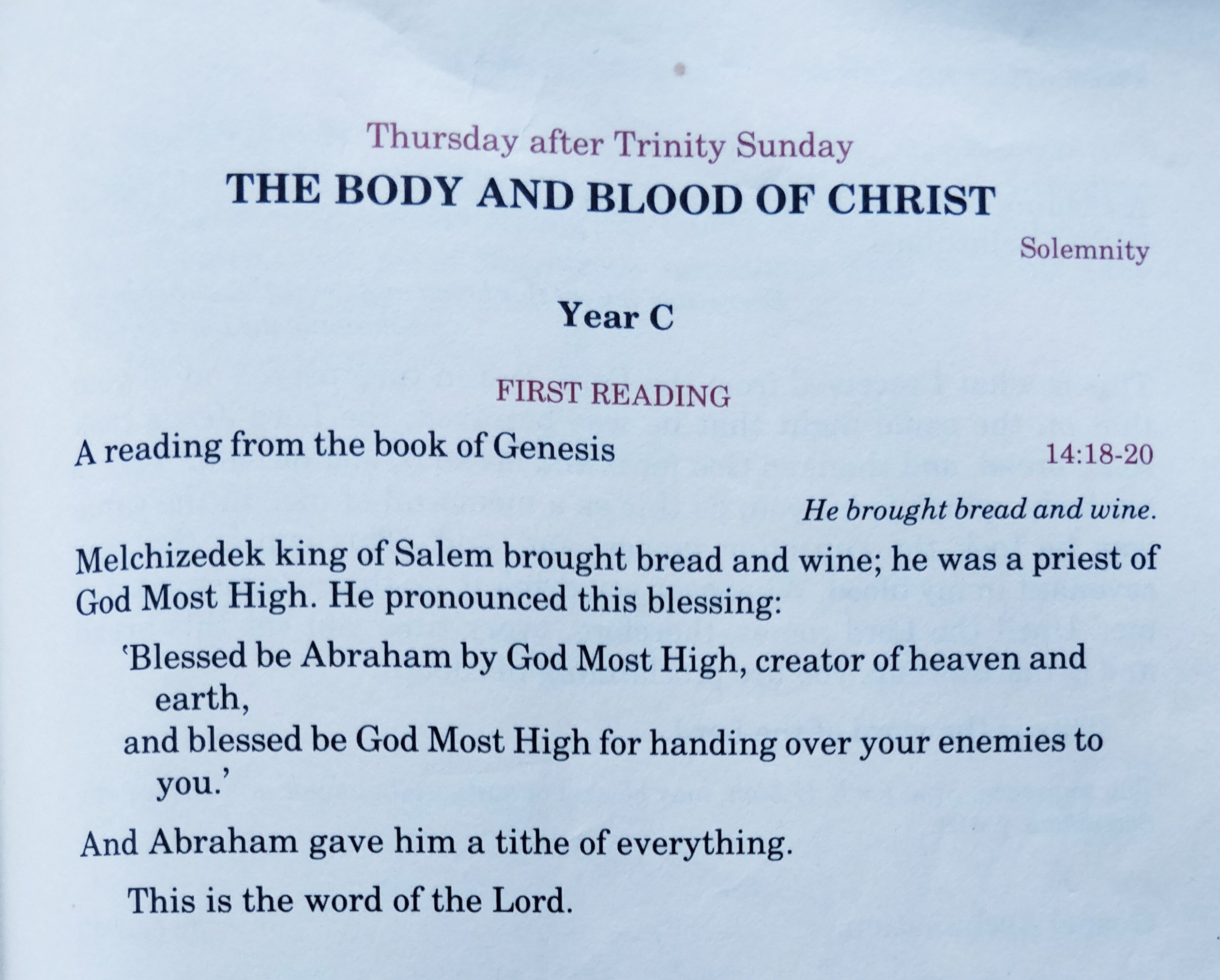

What’s wrong in this photo, which is of the Jerusalem-version lectionary used in England and Wales?

It occurs twice. Can you see it?

It’s “Abraham.” Abraham is wrong. It should be Abram, not Abraham. The patriarch’s encounter with the priest-king Melchizedek in chapter 14 of Genesis predates his covenant with God and the attendant change of his name from Abram—“exalted father”—to Abraham, “father of many nations” (Genesis 17:5). The use of Abraham in the reading at Mass for Corpus Christi in year C is anachronistic. OK, fair enough—but so what? It is just a name, and after all it is the same person. Why is the name so important.

Anyone who has even a passing acquaintance with the Bible should know at least instinctively that names are very important. Just today, the Birthday of John the Baptist, the saint’s name is at the heart of his identity and his father Zachariah’s well-being. For the patriarch, the name Abraham presages that though salvation will come by the Jews, it will not be for the Jews alone, but for all nations. The new Israel will no longer be an ethnic nation but a universal, multi-ethnic Church.

However, and of high significance for the feast of Corpus Christi, this mistake undermines the significance of Melchizedek, the mysterious king and “priest of the most high God,” whose brief encounter with Abram is recalled on the feast. Melchizedek’s name is also significant.

Melchizedek, “king of righteousness,” is the king of Salem (not yet become the holy city Jerusalem, “city of peace”). His name appears only once more in the Old Testament, in Psalm 109 (110), which is always interpreted in Christianity as a psalm referring to the Christ. Otherwise he is absent, until the Letter to the Hebrews in which St Paul (yes, I am for Pauline authorship) revives the memory of Melchizedek. In Hebrews 7 especially Paul notes explains how Melchizedek is without genealogy or history, no birth or death is recorded of this figure who could bless Abram and receive from Abram homage in the form of a tithe of all the patriarch’s goods. Melchizedek is obviously superior to the victor Abram.

For Paul, the well-versed Pharisee, Melchizedek is clearly a forerunner, a type, of Christ, the uncreated and deathless Messiah, whose priesthood must also be eternal, a “priest like Melchizedek of old” as the Psalmist prophesies. His priesthood is not that of Aaron, the brother of Moses, who was the first high priest and the father of the Jewish priesthood. In the Jewish sacrificial system animals and produce were offered, but never bread and wine. Christ’s use of bread and wine is thus alien to the Jewish system, but wholly consistent with the practice of Melchizedek.

Christ took bread and wine and offered them, like Melchizedek. But at the Last Supper Christ revealed that they were no longer to be seen as bread and wine; they become his Body and Blood by being associated, through the ritual offering, with the perfect and final sacrifice for sin, Christ’s Body and Blood on the Cross. Melchizedek’s priesthood is is thus both revealed and fulfilled in Christ.

What has this to do with Abram/Abraham? Well, the encounter between Melchizedek and Abram occurs before God enters into covenant with Abram, so making him Abraham. The sacrifice, the blessing, the identity of Melchizedek all pre-date the series of covenants that establish the Jewish nation and its law. Melchizedek is beyond these covenants, before them and more fundamental than them, a clue written into human history by the great Mystery Author himself, God. Melchizedek’s priesthood comes before the Jewish priesthood, and re-emerges after the Jewish priesthood falls—it is eternal whereas the Jewish priesthood has been provisional, a stop-gap for pre-messianic times. Only with Christ can we perceive the clue; Paul did and explains it.

Before Abraham, and all the Jewish Law and nationhood, there was Christ in the figure of Melchizedek, whom Abram served that day, and to prepare for the revelation of whom the whole Jewish nation and its Law was founded. Melchizedek is the sign of the eternal covenant in Christ’s body and blood, veiled beneath the forms of bread and wine.

That is why Abraham is so, so wrong in the lectionary. There is too much in this name to get it wrong. If you have a lectionary with this error, ask your priest to correct it.

It is such a strange error—repeated twice in the same reading so clearly no typo—that I am left wondering if an editor of this edition of the lectionary decided that the great unwashed would be confused to hear “Abram”; and so, for ‘pastoral reasons,’ he changed it to Abraham: it’s the same guy after all!

Well, no, in so many important ways it is not the same guy. Abraham is vastly different to Abram, just as Paul was so vastly different to Saul.

Shared on Facebook. Thank you for reminding us in the midst of all the horrors that this was all planned!

I noticed the Abram in the first Reading from Genesis yesterday. We use the NAB in the USA for the readings. The Lectionary we use to prepare for reading also has Abram. A friend of mine is a convert from Judaism and the change of his name from Abram to Abraham has great meaning for her. It is one of the reasons she became a Christian.

I am clear that the mistake is found in the English & Welsh lectionary, Jerusalem version. I know all the others are correct.

I think I agree with you, but didn’t Paul make the same mistake in Hebrews 7?

On what exactly do you “think” you agree with me?

That the line of Melchizedek is different from the line of Aaron.

Ah, then you do not need to hesitate. Melchizedek’s priesthood is entirely different from Aaron’s. This is not a matter of my private opinion but Christian faith.

As to Hebrews 7, Paul is using Abraham to cover both stages in that man’s life. What he does not do is quote the precise verse of Genesis and substitute Abraham for Abram. But I agree, Paul’s point is weaker because of this. Perhaps, though one trembles to suggest it, this precise nuance in name had not yet struck him? Pax.

I have searched in vain Father as I had actually read a verse this morning which referred to Abraham as Abram as well… and I thought to myself…”Abram, that must be a ‘before’ name reference”…

Well, I’ve gone back looking for where I read it…was it in the daily offering, was it from a verse on someone’s blog?? but I can’t find where I read it. I do know that it was before I read your post because I was hit by the striking similarities of thought… the second mentioning in one morning of the same name…the before and after as well as the mistake in the lectionary.

Names are important…especially as we see in both old and new testaments…

I have been on a bit of a personal quest that I’ve shared on and off in my own posts regarding my adoption 60 years ago.

Names, those before and after have been nagging me…but in your post and your

explanation of the importance of the before and after of Abram and Abraham—it resonated in me as to my own before and after…

So please know that I love the teaching you have offered here and will share it if that’s ok, tomorrow over on my little site as it relates to my own quest.

All blessings on your quest. If anything I write is useful, it’s all yours. Pax!

Thank you Father

Actually it should be “Avrum.” Abram is already an Anglocizing of the name.

Vs and Bs are a rather fluid thing in Hebrew when it is transliterated into English. The desert in southern Israel can be rendered quite correctly as either Negeb or Negev. Abram or Avram; both are valid. Tradition has opted for Abram.

And in similar vein, there is the covenant with the whole of the created world enacted with Noah after the flood, which precedes even that with Abraham.

Yes, but it is not centered on forming a chosen people or a sacrificial covenant as directly. Alas the symbol of Noah’s covenant has been hijacked.