DOM GREGORY MURRAY (1905-1992) of Downside Abbey was one of the great monastic musicians of the twentieth century. His organ works are held in especial regard, though he was no slouch on the chant. On the other hand, he prepared so comprehensively for the introduction of the vernacular in to the liturgy that he had everything ready for Downside to embrace from the outset a wholly English office. Years ago I heard a monk describe Murray as having been the rudest man in the English congregation. I cannot make a judgment on that claim.

Nevertheless in an exchange of letters in The Tablet in 1937 we can see that as a precocious young monk he was prepared neither to don velvet gloves nor to sugar his speech.

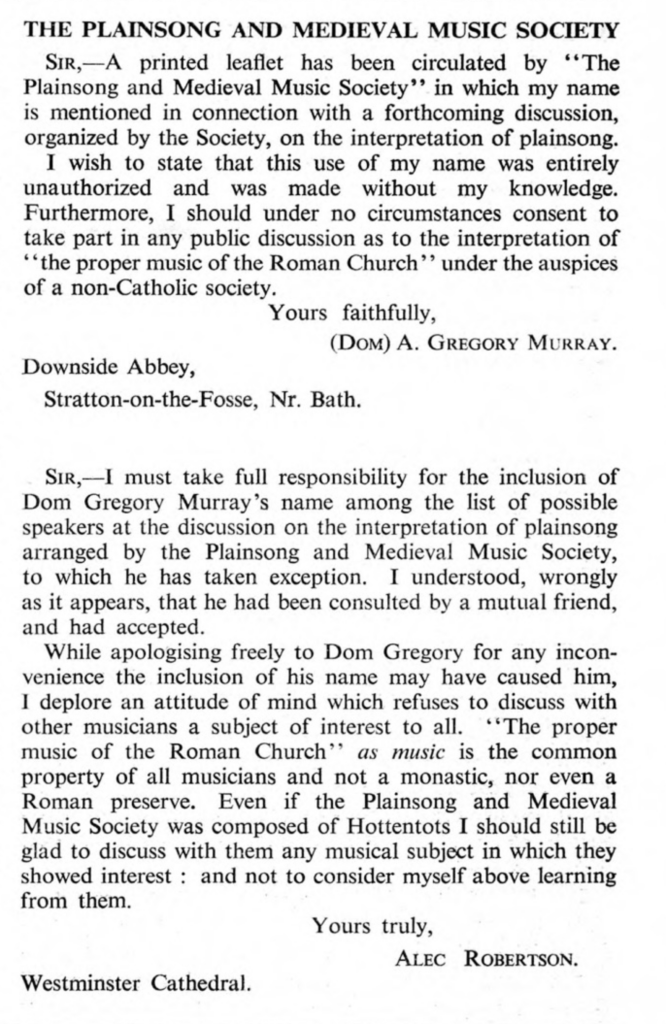

The contretemps begins in the 2 October edition of The Tablet, when Dom Gregory takes issue with some ecumenically-minded Protestant musical types:

Clearly the editor informed the relevant party of the transgression, and Fr Alec Robertson (1892-1982), then a chaplain at the cathedral in London, confessed to his error. However, he undercuts his confession and compounds his sin by taking issue with Dom Gregory’s brusque dismissal of any worth to be found in an ecumenical approach to plainchant. Chant is not a common Christian heritage for Dom Gregory, but the property of (ie, it is proper to) the Catholic Church of the Latin rite. Fr Robertson looks to it on the purely musical level, and music is a common heritage in his eyes, held even with Hottentots such is his largeness of spirit.

The bear had been poked.

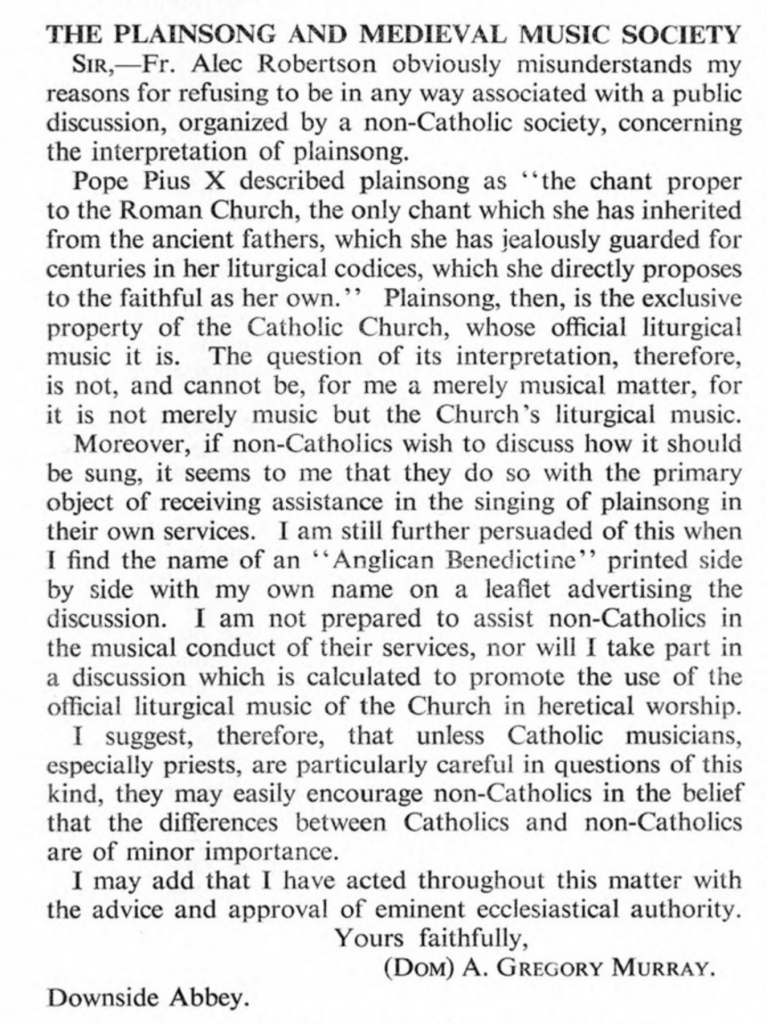

The 9 October edition of The Tablet carried Dom Gregory’s riposte:

Dom Gregory will have none of Fr Robertson’s ecumenical spirit. Plainchant is, by inferring from papal decree, the “exclusive property” of the Catholic Church, and it is She alone who regulates it and She alone who may rightly use it. He, no doubt correctly, deduces that the conference in question seeks to introduce chant into Protestant worship, but the Church’s “official liturgical music” has no place in “heretical worship.” Dom Gregory has a more fundamental issue in mind: the danger of appearing to accept the minimisation of differences between Catholic and non-Catholics. If not kind, Dom Gregory was certainly clear.

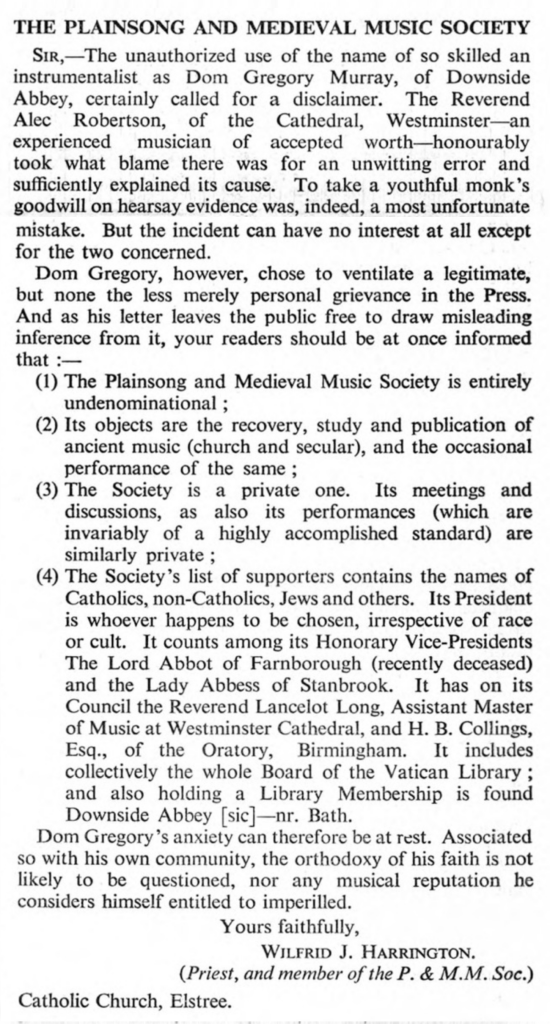

However, not everyone was ready to allow him to make this an ecumenical flashpoint. On 16 October two letters in reply were published by The Tablet. The first was

Say what he like about chant, Dom Gregory was not going to be allowed to define the identity of the Plainsong and Medieval Music Society. A member of the Society, and a Catholic priest himself, asserts that the Society is strictly non-denominational, and has many eminent Catholics as its members, not least Dom Gregory’s own monastery. Of course, Fr Harrington evades Dom Gregory’s principal, and technically correct, claim, namely that the society is non-Catholic and that, its share of Catholic members notwithstanding, it furthers aims that are not those of the Catholic Church at that time. Fr Harrington shows himself able to fire off a barb himself in Dom Gregory’s direction, referring to the freedom from danger of “any musical reputation he [Murray] considers himself entitled to.” Considering that Dom Gregory was making a stand (however indiscreet) on doctrinal grounds, this implied charge that he suffers from musical hubris is, perhaps, something of a cheap shot.

Immediately following is a letter from the Society’s Honorary Secretary, Pearce Hosken:

Mr Hosken is equally aggrieved but without Fr Harrington’s (or Dom Gregory’s) acerbity. It seems that both parties—Dom Gregory and the Society—are arguing at cross-purposes, at least to some degree. Both Mr Hosken and Fr Harrington have not addressed either Dom Gregory’s factually correct assertion that the Society is non-Catholic; in claiming to be non-denominational or even non-religious they implicitly admit it is non-Catholic by definition. They also fail to address Dom Gregory’s hardline assertion of the Church’s rights over its chant. Instead they focus on chant as the subject of academic interest.

And here Dom Gregory misses a point: anything Catholic can be the object of non-Catholic academic interest. One does not need to be Catholic to be able to study Catholic doctrine and have opinions on it. However, Catholic doctrine seen as an object of academic enquiry is not the same as situating and interpreting it within its Catholic context, which is the proper aim of theology per se. He we find the persistent contrast between theology and comparative religion: the former is undertaken within a context of faith, the latter within the context of purely academic enquiry.

Dom Gregory did not continue the exchange, possibly because he saw it as fruitless, or perhaps because his abbot advised him against it. While this exchange does show the vaunted acerbity of Dom Gregory, he does have something of a point about plainchant. While it may, like any thing else, be susceptible to forensic, external observation and description, as a living component of the Church’s worship perhaps it can only be interpreted adequately within its proper liturgical context, and by those who employ it in this context.

Even though Dom Gregory might be rude, might he not also, perhaps, be right? May he rest in peace, and his antagonists too.

I used to like to hear the odd bit of Gregorian chant on Radio 3, driving in the car or whatever. Ever since becoming Catholic and hearing – even trying myself to sing – it in the liturgy, I utterly recoil from the notion now. It really is the beating heart of sacred worship in music, and belongs nowhere else. I instinctively side with that troublesome monk

Certainly Murray had a point, all the more zealously held as it pertained to his daily fare not a mere hobby or passing fancy, as it would have been for the probable number in the Society who could be classed as dilettantes. However nothing is so sacrosanct that others cannot express an interest in it, even a fascination. Who knows but that it might be a way into the Church. But Murray was surely reasonable in not wanting to be associated with it and for stating his reasons why. That he needed to be so tart about it is questionable. Then again, perhaps he was rather sick of Anglo-Catholics and what he would have seen as their liturgical play-acting. It is hard to access the ecclesiastical atmosphere of 1937 from this distance in time.

Isn’t it? I’ve become aware of how precipitous was the decline in Anglo-Catholicism in the last century, after having seen itself as the future of that ecclesial community up until WW2. I had zero contact and little awareness of it in my Evangelical days. As a Catholic now, and knowing a few ex-Anglican Ordinariate priests, I’m even more baffled

The 1930s do seem to be another world. In too many places, including my home town, it is the Anglicans who are keeping plainchant and Latin polyphony alive while the Catholic churches drown in a sea of Haugen and Haas.

Alas, you have alighted in a bitter irony. Pax.

Of course, this is early Dom A. Gregory Murray, before he became involved in the Great War between the monks of Solesmes and the evil Mensuralists. Though I prefer the term Proportionalist (since proportional rhythm does not require to be mensural, i.e., to have a regular meter), I count myself among that latter impious lot, as did Dom AGM. I was saddened to hear from a former professor that Murray was silenced by the order in his last years and was not permitted to talk about the Chant because of his “un-Benedictine” views. Well, the wind is changing . . .

Gregory Murray sold the musical pass by composing the bland and pedestrian “People’s Mass”, later fitted to the traditional Anglican words as “A People’s Communion Service” (some irony here, although the adaptation was wrought by another hand), and later still made slightly more tuneful and rearranged to the ICEL forms. More irony: since the retranslation of the Montini Missal this version is no longer useable in the RC Church, but continues to thrive in Anglican churches (where it has always perhaps been anyway more popular).

Dom Gregory Murray, I believe, sold another pass when he refused to attend his own brother Fr Joseph Murray’s Requiem Mass and funeral – it was to be in the New Rite, but in Latin and probably sung (I am not certain)with Gregorian Chant. By then, of course, it was Post-Vatican II fun times and Dom Gregory was now hating Latin and the chant. The Party Line had changed and so had he.

“Behold, how good and joyful a thing it is,brethren, to dwell together in unity” (Psalm 125 ,Anglican translation ! of course) His view of Anglican services was hardly likely to produce the oil of charity which could have converted them, but then he was probably only interested in defending the tribal reservation.