LET’S BEGIN WITH the Masses. I mean not the proletariat of course, but the sacred liturgy. It seems that Mass is yet again le sujet chaud. Only because there is a rumour, the heat of which has been increased by the appointment of Archbishop Roche as Prefect of Divine Worship, that the Extraordinary Form of the Mass (until very recently the only form) is to be forbidden again. The mechanism suspected is an abrogation of Benedict XVI’s Summorum Pontificum.

Given the incomprehensible, indeed incredible, prohibition recently of so-called private Masses at St Peter’s in Rome, a fantastical rumour that turned out to be accurate (though the act is arguably illegal), the fears are not irrational. Yet one can hope they are unfounded. It would be a remarkable own-goal should an attempt to inhibit the old Mass be repeated. As Rome, including Pope Francis, is battling to avoid the schism that looms on the horizon with the upcoming German general synod, to forbid the old Mass would be to throw a match into the ammunition dump marked ”schism.“ For what good purpose? To champion the Ordinary Form of the Mass? To make the Mass the cause of schism would be as good as sacrilegious. If the Ordinary Form really needs such draconian measures to bolster its uptake then there is an elephant in the room that needs to be dealt with. Then we have the utter absurdity of portraying as divisive the Mass that served, united and nourished the western Church for a millennium and a half. There is a loud faction in the Church that cries for liberty in morals but rigid uniformity in liturgy.

The uniformity is not in the official rite of the Ordinary Form, but in its utility as an umbrella that covers a multitude of ”styles“ of celebration. With its indulgence of many and various official options within the rite, it effectively sanctions any option in practice because the operation of options has become normative. Gelineau was correct when he declared that, with the imposition of the new Mass, the Roman Rite was dead. We now have almost as many de facto rites as there are places where the Ordinary Form is celebrated. It is, in the truest sense of the word, anarchy. This is due to the new liturgy having made every priest his own pope with regard to the Mass. So often, narcissism runs close behind, both with the progressives and, more often than we might expect, with the trads and conservatives. What is there for real, enduring unity, in this chaos.

The problem is that in seeking to fix the problems we exacerbate them. The process manifests itself as but the latest in more than half a century of constant liturgical change. In seeking to correct the instability that now afflicts the liturgy, the repairers merely entrench the instability.

To be honest, I have never offered the old Mass, and have only once assisted in it as a minister. However, to portray the Mass that saw the Church through thin and thin (the thick was rarer than we think) for so many centuries as something to be derided, sneered at, and outlawed is, quite simply, an act of self-defeating insanity and stunning illogicality. Our liturgical and eucharistic spirituality and theology is mostly predicated on it. To deny it is, at bottom, to deny our own identity.

That said, I was raised with the new Mass. I am comfortable with a decorous vernacular (though the too-often trite banality of the first English missal and the Jerusalem version of the bible in most non-American lectionaries does not rate as decorous), and with an ars celebrandi that adhere to the rubrics. I value the enhanced role of the homily, though its potential is not adequately realised given some of the homilies I have heard in my 50-odd years. Simplification has offered real fruit, though it has unwittingly enabled vandalism in both ritual and architecture. Moreover, it is clearly not the Mass envisaged by the Fathers at Vatican II. To call it the Mass of Vatican II, even when celebrated properly, is to stretch credulity to breaking point. The closest we got to such a Mass was between 1964 and 1969. Yet it cannot be denied that ore than 2000 bishops, the overwhelming majority, sanctioned some degree of revision of the liturgy, and the Mass not least.

Thus, our conundrum. Reform was sanctioned, so whatever the reform that came to be dished up five years later is held up as demanding acceptance lest we reject Vatican II. The reformed rite is inescapably unstable, and every attempt to fix it risks aggravating the instability. The new Mass was portrayed as a liberalising, liberating reform that served the people, yet the people have abandoned it in steadily increasing numbers year on year. To shore it up, the illiberal and oppressive mechanism of forbidding almost any alternative has been employed.

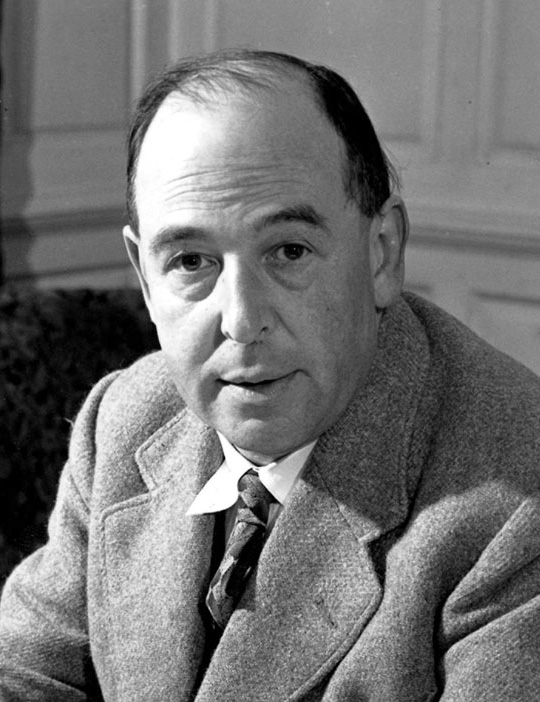

In 1963 C S Lewis (above) published his Letters to Malcom, Chiefly on Prayer. Written in an Anglican context, it is remarkably prescient about the liturgical chaos that would soon be unleashed in the name of the Council that was then in session.

It looks as if they believed people can be lured to go to church by incessant brightenings, lightenings, lengthenings, abridgements, simplifications, and complications of the service. And it is probably true that a new, keen vicar will usually be able to form within his parish a minority who are in favour of his innovations. The majority, I believe, never are. Those who remain—many give up churchgoing altogether—merely endure.

Is this simply because the majority are hide-bound? I think not. They have a good reason for their conservatism. Novelty, simply as such, can have only an entertainment value. And they don’t go to church to be entertained. They go to use the service, or, if you prefer, to enact it. Every service is a structure of acts and words through which we receive a sacrament, or repent, or supplicate, or adore. And it enables us to do these things best—if you like, it ‘works’ best—when, through long familiarity, we don’t have to think about it. As long as you notice, and have to count, the steps, you are not yet dancing but only learning to dance. “A good shoe is a shoe you don’t notice. Good reading becomes possible when you need not consciously think about eyes, or light, or print, or spelling. The perfect church service would be one we were almost unaware of; our attention would have been on God.

But every novelty prevents this. It fixes our attention on the service itself; and thinking about worship is a different thing from worshipping…

A still worse thing may happen. Novelty may fix our attention not even on the service but on the celebrant. You know what I mean. Try as one may to exclude it, the question, ‘What on earth is he up to now?’ will intrude. It lays one’s devotion waste. There is really some excuse for the man who said, ‘I wish they’d remember that the charge to Peter was Feed my sheep; not Try experiments on my rats, or even, Teach my performing dogs new tricks.’

I can make do with almost any kind of service whatever, if only it will stay put. But if each form is snatched away just when I am beginning to feel at home in it, then I can never make any progress in the art of worship. You give me no chance to acquire the trained habit—habito dell’arte…

And anyway, the Liturgical Fidget is not a purely Anglican phenomenon; I have heard Roman Catholics complain of it too.

And that brings me back to my starting point. The business of us laymen is simply to endure and make the best of it. Any tendency to a passionate preference for one type of service must be regarded simply as a temptation. Partisan ‘Churchmanships’ are my bête noire. And if we avoid them, may we not possibly perform a very useful function? The shepherds go off, ‘every one to his own way’ and vanish over diverse points of the horizon. If the sheep huddle patiently together and go on bleating, might they finally recall the shepherds? (Haven’t English victories sometimes been won by the rank and file in spite of the generals?)…

I think it would have been best, if it were possible, that necessary change should have occurred gradually and (to most people) imperceptibly; here a little and there a little; one obsolete word replaced in a century—like the gradual change of spelling in successive editions of Shakespeare. As things are we must reconcile ourselves, if we can also reconcile government, to a new Book…

Yet we all want to be tinkering.

__________________________

”What on earth is he up to now?“ Indeed. That was my thought in the wake of the pope’s rejection of Cardinal Reinhard Marx’s resignation a few weeks back. The jarring note as it was publicly announced was the lack of an equally public acceptance of it by the pope. Why wasn’t it announced after it had been accepted? Why announce a resignation before it is signed, sealed, delivered…and accepted? There was the whiff of PR spin and strategising about it all.

So it was no surprise when the pope’s equally public refusal to accept the resignation was released. It had the look of a cynical charade. This is not the look the Church needs now. Tactically, it strengthens Marx’s hand in the upcoming German Synod, which seems to have the potential to provoke a schism of the sort we have not see for a long time.

However, there could be deeper levels to all this, not obvious, and perhaps unexpected. One could see the pope’s refusal to allow Marx to jump ship now as a way of making him take primary and active responsibility for the outcome of the synod: you started this mess, you finish it. This is not so fanciful given Cardinal Kasper’s recent expression of alarm at the direction the German synod is taking. Kasper is no conservative. He is very much a Pope Francis man. It is almost inconceivable that Kasper spoke without some consultation with Pope Francis. In a sense, Kasper may been an unofficial papal spokesman in advance of the synod. It is an indirect warning shot across the synodal bow.

Moreover, given the references to the child abuse crisis in the German church, it is not inconceivable that Pope Francis is not allowing Marx to evade facing the music for the German church’s misdeeds. As bishop of Trier, Marx did not cover himself in glory in his response to allegations of abuse. While he is still in place as archbishop of Munich Marx cannot pass the buck to a hapless successor.

So while one cynic might see the recent papal-Marxian manoeuvres as a ploy to strengthen Marx’s hand at the synod, another cynic might wonder if the pope is at best forcing Marx to take responsibility for his various decisions, or even setting him up as a fall guy when the synod goes feral and the abuse crisis goes bang.

So be it the machinations on the Mass or Marx’s ecclesiastical manoeuvres, with Lewis I am left wondering, what are they up to now?

Interesting recent article from Dom Alcuin Reid in which he makes the point that P VI said the loss of Latin, chant, the old Mass were means to and end, the price worth paying for the advantages the NO would bring. As these advantages have failed to materialise the entrenchment of the NO has become an end in itself, both to attempt to disguise the failure and to avoid facing the logical consequence of such acceptance

Well spotted. In my haste I had forgotten Dom A’s article.

Since you have kindly followed my various blogs down the years – and occasionally commented or liked posts there – you will be aware of my support for traditional Catholicism for much of the past decade. So, you might permit me to suggest an alternative view to your proposal that a reversal of Summorum Pontificum would be “to make the Mass the cause of schism” and the potential sacrilege would be the result of the reform of the Motu Proprio by Pope Francis.

When Pope Benedict XVI made this initiative he did not propose it as a rallying point for those dissenting from the post-Council liturgy, but suggested that it could enrich our understanding of it and the two would work together in a symbiotic way. That is not what happened, and it would be fair to say that extreme radicals have rallied around the ‘Extraordinary Form’ as a standard held high for a variety of political causes, some of them deeply unsavoury, even quite offensive. Pope Francis may rightly feel that a limitation of the EF would help to dampen down the radical dissent which is already threatening schism. I don’t think it will succeed in doing that, but will simply pour petrol on the flames, but who am I to judge? 🙂

My point is that his reaction is predictable, equally perilous as the actions of those who have already rejected papal teachings and the Magisterium, and I am not convinced that this will turn out well! What I do know is this. When the ‘traditional’ blog that I helped found and used to write for (Catholicism Pure & Simple) went beyond mere criticism of Pope Francis and rejected him entirely; when the alt-right of Steve Bannon and Trumpism became standard fare, instead of Catholic spirituality; when dangerous anti-vaxxer lies and the paranoia and conspiracies of Viganò became an alternative ‘magisterium’; then, apart from sitting here looking open-mouthed in disbelief at my computer screen, there was nothing else for it, but to fully back Pope Francis for the sake of remaining Catholic and obeying the very principles that I learned when I converted from the Church of England.

I regard your voice as one of the more sensible traditional positions. Since I now write for Where Peter Is (I have a regular Monday series “Postcards from the Camino”), I am more than happy with the company I keep now, and I see my ‘traditionalist years’ as a descent into a nightmare that I was only too glad to wake up from! I only have to look at CP&S now to remind myself how far down the rabbit hole things have gone! Much of what we experience in the Catholic Church in Europe – in social media at least – is driven by the political warfare that now takes the place once occupied by American democracy. Both the political system and the Catholic Church in the USA have run out of energy: in cultural terms they are both in decline. That much is obvious. Their negativity is feeding off each other.

I am as alarmed as you by the Pandora’s box that may be opened up by the German synod, and I am in full agreement with the idea that “the pope is at best forcing Marx to take responsibility for his various decisions, or even setting him up as a fall guy when the synod goes feral and the abuse crisis goes bang.” Cardinal Kasper is certainly the key to this (and far more experienced than Pope Francis, by the way, as I was reminded as I wrote my piece about ecumenism and Taizé yesterday for WPI https://wherepeteris.com/postcard-10-taize-a-parable-of-communion/

The question is no longer, which tribe do I support? The urgent question is how we help the Pope bring the Body of Christ together, in unity. We don’t help by identifying as traddies or liberals. As we Compostela pilgrims say, Ultreïa et suseia, forward, and alleluia!

Thank you, Gareth, for a lucid and balanced exposition of your outlook on the ecclesiastical status quo. I concede that my following of blogs is now vastly reduced precisely for the reason you adduce: so many were becoming toxic for me, some unwittingly. I will look up WPI and see if I can settle that into my feed.

Most of your outlook I share. As early as St Paul we were warned against parties and factions that weaken the Body of Christ. Increasingly I find it easier to eschew and avoid the factions today. My focus is on doctrine and practice, worrying about my own grasp on them, not looking too often at others’. Whie I conder the new Mass, as it is, flawed to a great degree, I do not see the solution being a complete return to 1962. Of course, as you will know, 1962 is no longer adequate for many. Pre-1955 for Holy Week, or even pre-1948 for everything, as it is pre-Bugnini, who is portrayed as something akin to the Antichrist. He was a schemer, I have no doubt. But he did not convince 2000+ council fathers to call for some liturgical revision. Alas he had to great a hand in the implementation of the conciliar mandate, but even in that he was not alone. But we must have a scapegoat.

That is why I look to the interim rites after the Council. They follow faithfully the conciliar will as it was expressed; they maintain the essential elements and tone of traditional liturgy. Archbishop Lefebvre was happy to use them until he crossed the Rubicon in 1988.

Pope Francis exasperates me, but he is the pope and to hear the way people speak of him is distressing at times. Some of them are crytpo-Calvins in their rhetoric. He is surrounded by an uninspiring crew, but how many popes before have also reigned, rather than ruled, over a dissolute court? His intentions are mainly sound but his lack of experience of Rome, as it actually functions, is all too apparent. There is something to be said for electing curial cardinals, like Benedict XVI. For a start, they have less of a desire to be the world’s parish priest. There is much to be said for the days when popes were rarely heard, and more rarely seen.

Of course, when has the Church militant been anything other than flawed even as it is faithful? The grass was never really greener in another age. The specifics may differ but the struggle is consistent. The Church has ever had one foot in heaven, and the other in the dungheap.

So, to use that tired proverb, I try as much as I can to light a candle rather than curse the darkness.

It was good to hear from you.

Pax.

Thanks to Dom Hugh and Gareth for sensitive and thoughtful reflections. It is important in the present environment that the traditional liturgy should not become the preserve of right-wing extremists. Hence the importance of mainstream figures such as Archbishop McMahon of Liverpool being prepared to celebrate it.

Archbishop McMahon is a Dominican and heir to some of the tendencies to social radicalism in his province. In that context, the writings of Anthony Archer OP in the 1970s (published with the support of Herbert McCabe*) make interesting reading:

http://www.lmschairman.org/2013/06/a-sociologist-on-latin-mass.html?m=1

Archer harnessed the language of Marxist sociology to document the distress of the old working classes in the North about having the Latin Mass and its spiritually torn away from them by a hectoring and.imsemsitive.new.middle class in the 1960s and 70s.

That is still a problem in too many parishes. Any attempt at mutual enrichment as proposed by Benedict XVI will be fought to the death by an entrenched clique of baby boomers for whom it will always be 1971.

* Herbert was fiercely Old Left in his politics but a devoted and acute student of St Thomas and no liturgical radical. He thought that the reductionist rites, banal suburban English , strumming of guitars and singing of children’s songs had betrayed the intent of the Council, and that the traditional Dominican Rite was in some ways closer to what the Council Fathers really intended.

A true liberal, of course, could cope wire happily with either the old or new Mass. That’s why, despite an irony now more clearly apparent, I prefer to call the so-called liberals progressives.

Archer is new to me, so thank you for the link. I can agree that the reform as we got it was a bourgeois triumph. More than once I have lamented the official vandalism, even destruction, of beautiful churches so often built and outfitted on the pennies of the poor – ruined with usually no say allowed them at all. Father knew best. If that wasn’t clericalism, what was?

Thank you for your comments, Brother Hugh, and yes, do take a look at Where Peter Is.

What you say, PM, reminds me of my Anglican days and it was always clear that the High Church tradition in the East End of London – for example – went together with a very politically progressive outlook. That is well documented and it was still more or less visible as late as the 1980s. The older brothers in the Anglican religious communities would mention ‘The Party’ when it came to election time, and there was only one party, the Labour Party. Yet they were all dedicated to the idea that the real Anglican ‘Alternative Service Book’ was the Roman Missal!

Insensitive, not ‘imsemsitive,’. My apologies.