FOR THOSE STRUGGLING to remember it, the Law of Unintended Consequences is a sociological maxim, with origins in the thought of John Locke, which holds that a positive, deliberate act of one kind or another may result in unintended or unforeseen outcomes. These outcomes fall roughly into three categories: unintended/unforeseen benefits; unintended/unforeseen drawbacks; perverse outcomes (that is, when the act exacerbates rather than resolves the issue in question).

Keep this Law in mind.

We might be in a position already to foresee what some things the author(s) of Traditionis custodes (TC) apparently did not foresee, let alone intend.

Collegiality

On Facebook, which correctly and responsibly used can be a very helpful tool, users have been posting the letters from their local bishops in response to the motu proprio, mainly American ones. They all have a similar basic theme: we need time to reflect on this and work out how best to implement in our dioceses, so for the time being nothing changes. Examples include Archbishop Sample, Archbishop Cordileone, Bishop Hying, even Cardinal Gregory.

This approach, of course, is entirely consistent with Article 3 §4 of TC, which requires those priests delegated by the bishop to exercise pastoral care for the flocks which adhere to the old books. How much more is this required of the bishop himself, and not just his delegate.

Indeed these bishops seeming to be adopting a pastoral tone that is in marked contrast to the “paternal solicitude” (TC, preamble, para 2) of the motu proprio.

Moreover, if a bishop decides to leave things unchanged in his diocese, he is justified by the letter of TC, to wit Article 2:

It belongs to the diocesan bishop, as moderator, promoter, and guardian of the whole liturgical life of the particular Church entrusted to him, to regulate the liturgical celebrations of his diocese. Therefore, it is his exclusive competence to authorize the use of the 1962 Roman Missal in his diocese, according to the guidelines of the Apostolic See.

Note, it is now the diocesan bishop’s “exclusive competence” to determine what role the pre-conciliar liturgy plays in his diocese. Let that sink in. Notwithstanding the variety of episcopal temperaments and ideologies, if a bishop should want to keep things as they are in his diocese, he can, and without needing Rome’s permission.

In a stroke of the papal pen, the ersatz episcopal collegiality of bishops’ conferences is set aside in favour of the traditional and historic manifestation of collegiality: the bishop ruling, generally unfettered, in his own diocese. Corrective and moderating influences on this independence were exerted more usually by local synods (in the proper sense of the word, which refers to gatherings of bishops; the modern phenomenon of the diocesan or national “synod” is a misnomer—they are better termed plenary assemblies, as in Australia). Thus the local bishop was moderated by the college of the bishops of his province or region acting in synod, which was not a permanent body but existed only when convoked.

Did the pope/curia actually intend to enable authentic collegiality? Since the pope professes a high regard for sharing the governance of the Church with his fellow bishops, one might argue that perhaps this is an intended consequence. But that would require one to believe that the pope actually wrote TC, rather than merely signed it. It seems more likely that this revived and reinvigorated collegiality is an unintended benefit.

Reception

The concept of reception in the Church asserts that for a teaching or discipline to be effective in the Church it must be accepted (ie, received) by the Church. It was first articulated comprehensively by the great 12-century Bolognese canonist Gratian, in Distinction IV in his Decretum of 1140:

Laws are instituted when they are promulgated and they are confirmed [ie received] when they are approved by the practices of those who use them. Just as the contrary practices of the users have abrogated some laws today, so the [conforming] practices of the users confirm laws.

Over time, canonists saw reception as crucial to the validity of a law. In time they came to see that the validity of a law, whatever the authority of the one/s who promulgated it, required two essential characteristics: that its content be in accord with divinely-revealed truth, and that it be received in practice by the Church.

So a law, even promulgated by a pope or council, that was ignored in practice by the wider Church would in time be deemed as invalid.

If a majority of bishops, exercising authentic collegial authority, determined not to implement the precepts of TC in their dioceses, then this would raise the question of reception. No doubt, they might accept the motu proprio in theory, but in practice they would not be receiving its precepts.

However, reception is not confined to the apostolic college of bishops. It encompasses the whole body of the Church. We need only remember a little Newman to realise that the Arian crisis of the fourth century began to be resolved not by bishops—the majority of whom caved into the heresy of Arius—but the refusal of the faithful to accept Arianism.

Has TC, unwittingly, provoked a potential crisis in the reception of the precepts it contains? Are they substantially in accord with divine truth, in fact not just in assertion? Will those at whom they are directed conform to them—receive them? If the answer to either should turn out to be no, then the law of TC would inevitably be invalid. But that takes some time to determine, at least in the case of the second criterion. In this there is a deeper danger for authority: should it be determined to have acted invalidly, it undermines its own effectiveness in governing the Church. Here we return to the self-defeating own-goal idea.

Whether this would be an unintended benefit or unintended drawback is in the eye of the beholder for now, I suspect.

Licit liturgical books

At Douai, we use the 1934 Antiphonale Monasticum for vespers. We do so without any substantive modification—the reading is not in the vernacular, no intercessions are intruded, and so on. We use the reformed calendar, but this does not affect the conduct of the liturgy per se.

Yet, Article 1 makes assertions which are quite complex and need unpacking:

Art. 1. The liturgical books promulgated by Saint Paul VI and Saint John Paul II, in conformity with the decrees of Vatican Council II, are the unique expression of the lex orandi of the Roman Rite.

“Liturgical books” covers, on face value, more than the Roman Missal. A plain reading would conclude that it covers also the Divine Office/Liturgy of the Hours.

So, does this mean, given the provisions that follow, that Douai must seek permission of the bishop to use the old, pre-conciliar, antiphonal? There is mention only of bishops in TC, not of ordinaries, the latter category covering also religious major superiors such as Douai’s abbot. If the abbot had to seek the permission of the bishop for the performance of the monastic office, this would be a grave infringement on the ancient rights of exempt religious such as English Benedictine monks.

Was this foreseen by TC’s author/s? If not, then it would constitute, at least from a monastic perspective, an unintended drawback. Moreover, TC surely could not abrogate the historic rights of exempt religious, not as it is written, or so it seems to me. In that case, exempt religious with their own established liturgical customs, might not receive the motu proprio in practice. The potential implications were set out in the section above.

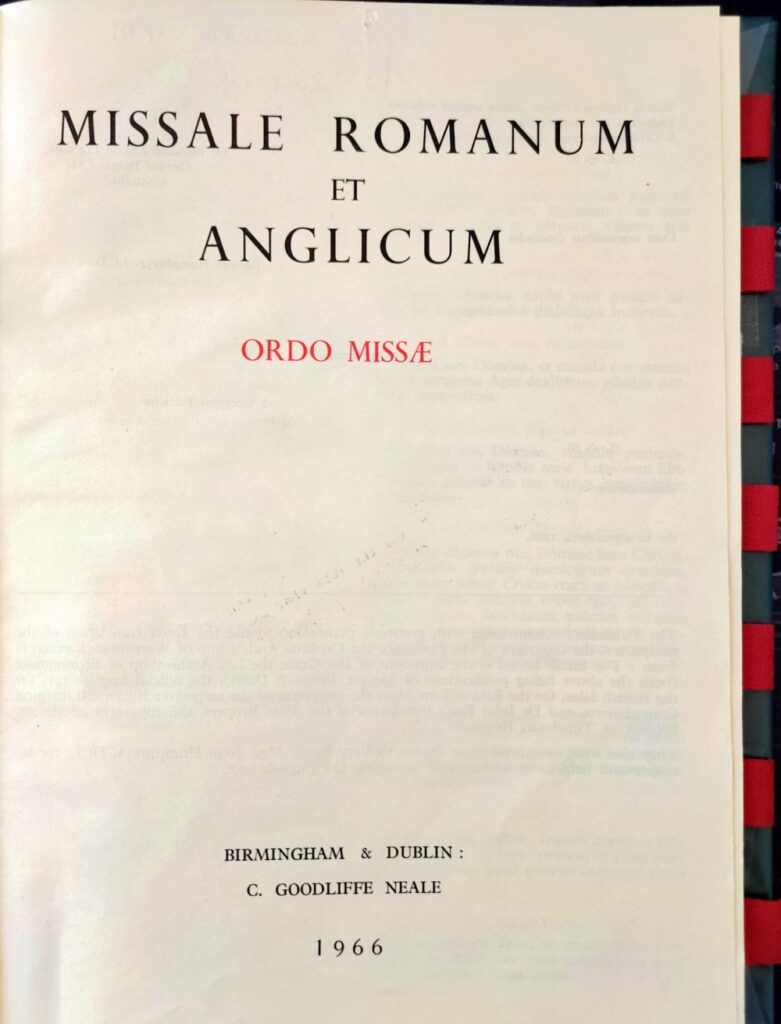

However, from my perspective at least, there may be here an unintended benefit. A friend—let’s call him him G for his own protection—asked if the Ordo Missae of 1965 (OM65)might now actually be available for unrestricted use. It conforms with Article 1 in being promulgated by Paul VI. It is absolutely post-conciliar, being the concrete fruit of Inter Oecumenici, the 1964 instruction on the implementation of the conciliar constitution on liturgical reform, Sacrosanctum concilium. It fits Article 1 neatly.

One might object that the preamble of Article 3 rules this out:

The bishop of the diocese in which until now there exist one or more groups that celebrate according to the Missal antecedent to the reform of 1970:…

This appears to specify the missals subsequent 1970 (remember we currently use Missale Romanum 2008, not 1970). Sed contra, the OM65 is not a missal at all. An Ordo Missae is the core of a missal in that it sets out the content of the ritual of the Mass, but it is not synonymous with a missal. OM65 is a reform deriving organically from the Missale Romanum of 1962 (MR62), but sits separate from it. It is not the same as, or part of, MR62.

Interestingly, the decree promulgating the OM65, Nuper edita Instructione, orders that the OM65 “be published and incorporated into any new editions of the Missale Romanum”. OM65 was held by the curia, and by implication the Consilium, to be the “prototype” serving “the overall rationale for the restructuring of the Mass.” This, alas, was not to be.

What I am struggling to find is a decree in 1969 or 1970 which abrogates any liturgical books coming before it. The Apostolic Constitution Missale Romanum of 3 April 1969 decrees a starting date for the new Mass as 30 November 1969, but it does not mention the abrogation of any previous books. The decree a few days later, Ordine Missae, which instituted a new Ordo Missae, markedly different from the “prototype” of 1969, and set the same date for its implementation but seems not to mention the abrogation of any previous Ordo. [If you can supply me with the reference to any such decree I would be grateful to receive it.]

Article 3 §3&4, and Article 5, make explicit reference to the Roman Missal of 1962 as that which is being newly regulated. However, OM65 is not part of MR62, so it falls outside this regulation in a plain reading of it. Moreover, given that Article 1 seeks to establish the “liturgical books promulgated by Saint Paul VI and Saint John Paul II, in conformity with the decrees of Vatican Council II, [as] the unique expression of the lex orandi of the Roman Rite”, I cannot see any restriction on use of the OM65, which was “promulgated by Saint Paul VI … in [more substantial] conformity with the decrees of Vatican Council II…”

So, the question arises here: is there here an unintended consequence (indeed, benefit from my perspective) of TC in implicitly liberating the OM65 for use as an expression of “the lex orandi of the Roman Rite”? If you can find a definitive answer to this, please share it here (not Facebook) for the benefit of myself and readers here. As one door has apparently been closed, another apparently has been opened.

Curiouser, and curiouser…

Now is the time to make a stocktake of our spiritual and liturgical outlook. Am I devoted to the liturgy of the Church in general, or to a specific missal of a specific date, over and above all else? Quite apart from papal or curial motivations, what might be the reason God has allowed TC to appear? Does my devotion to the Church’s liturgy end in a spirit of self-will or of authentic charity? Am I truly seeking first the Kingdom of God and His righteousness, confident that all other things needful will be supplied by God (cf Matt 6:33)?

Be assured I direct these questions first of all to myself, and to no one else in particular. It is just that it strikes me that times of trial so often contain a renewed call to repentance and conversion. Another friend reminded me of a post on my old blog when I wondered if Francis would be the “pope of our punishment.” It is a question that remains open.

Since what we need to do now, above all, is pray. those of you who are disturbed, or worse, might find some help in joining the prayer campaign launched by a friend of mine. It would be a positive step toward lighting a candle rather than merely, and futilely, cursing the darkness. You can join in by clicking here.

Pax.

Thanks again Father. This is very helpful in these troubling times.

Pax!

This is a very thoughtful and stimulating response to TC (in marked contrast to some of the reactions I have seen elesewhere) and it deserves a second reading. It also deserves to be shared more widely, which I shall do. Thank you.

You state: “if a bishop decides to leave things unchanged in his diocese, he is justified by the letter of TC, to wit Article 2:”. Yet in the following quote we read that it is the bishop’s “exclusive competence to authorize the use of the 1962 Roman Missal in his diocese, according to the guidelines of the Apostolic See.” Unfortunately, that final phrase suggests that the bishop cannot maintain the status quo if the TLM is being offered in a parish church, as the new Motu Proprio demands that the TLM not be offered in a parish church, and as this demand would seem to be part of the “guidelines of the Apostolic See.” Please prove me wrong.

Salve. I’ve little doubt you are right. It shows the in incoherence of the modern doctrine of collegiality in practice.

As the number of parishes dwindles in sync with the decline in clergy and congregation numbers, perhaps redundant, or superfluous, parish churches could be reclassified and so be open for the EF. That requires a sympathetic bishop of course.

I agree the Motu Poprio is poorly drafted and raises all sorts of questions as to just exactly how it could possibly work (quite apart from the ludicrous nature of the aim of ‘returning us’ all eventually, to the Novus ordo) .

On your concern in relation to the 1934 Antiphonale, though, isn’t the problem solved by the fact that there is no officially promulgated later Antiphonale for Benedictines? My understanding is that the liturgies of different monasteries, and the various chant books published by Solesmes and others to facilitate them are all authorised under the ad experimendum permissions given after Vatican II, so the 1962 breviary remains at least in theory, the only officially promulgated one for the Order, with the Antiphonale and earlier chant books to support it?

Salve. What, then, is the status of the new Antiphonale Monasticum of 2006 (which Douai experimented with, deciding to stick to 1934)?

I don’t have my copy of it with me, but from memory it says something like, designed to support those using versions consistent with the Thesaurus. I don’t believe it has any formal status beyond that.

Perhaps this pellucid passage from Evangelii Gaudium #223 will help us to elucidate matters:

‘One of the faults which we occasionally observe in sociopolitical activity is that spaces and power are preferred to time and processes. Giving priority to space means madly attempting to keep everything together in the present, trying to possess all the spaces of power and of self-assertion; it is to crystallize processes and presume to hold them back. Giving priority to time means being concerned about initiating processes rather than possessing spaces. Time governs spaces, illumines them and makes them links in a constantly expanding chain, with no possibility of return. What we need, then, is to give priority to actions which generate new processes in society and engage other persons and groups who can develop them to the point where they bear fruit in significant historical events.’

On the question of the Ordo Missae 1965, unless there’s a canonical abrogation that neither of us are aware of, it would seem the best course would be for priests to simply start using it (particularly those whose TLMs have been supressed by their local bishops). If it’s a canonical impossibility, that will soon become apparent. If not, well, we may have the Reform of the Reform from an unexpected source.

One question: how much work would have to be done in order to make the OM65 useable on a daily basis?