YOU DO NOT NEED me to tell you that we have just celebrated lamented marked 60 years since the opening of the first session of the Second Vatican Council. Much was hoped from it; much certainly resulted from it. We would be naive or even dishonest, however—whatever our outlook on things conciliar—if we did not accept that the results did not fulfil the hopes. Looking back after 60 years, our outlook is inevitably coloured by the experience of those six decades. Since all Catholics, progressive and traditional and in-between, seem destined to remain “prisoners of Vatican II” (to quote Ross Douthat in his recent New York Times article), it might be illuminating to cut away those decades awhile and try to place ourselves in the 60s. World, society, and Church were vastly, vastly different in those days, and rapidly changing. The Church of 1 January 1960 looks very different indeed to the Church of 31 December 1969. One little point of access is afforded by America’s Life magazine, a high-profile, highly-regarded, socially-influential medium of photo-journalism in its day. The 1960s were very much part of its “day.”

In the late 1950s and early 1960s the Church was a fairly regular presence in Life. Papal elections were covered, and sumptuous photo-portraits of the papabili cardinals presented to the world’s gaze. An interest of mine now is to see how the presentation and perception of the Church changed in the wake of the Council. So let us look for a minute at 1966. How was the Church being seen in Life that year?

In the 24 June edition of Life was an article titled “Challengers of Their Church: Restless Breed of Catholic Priests.” It profiles seven priests who were in hot water, as it were, with their bishops or religious superiors. Six of them were what we today would term progressive, and one traditionalist. That mix is itself interesting. Let’s meet them and hear a little from them:

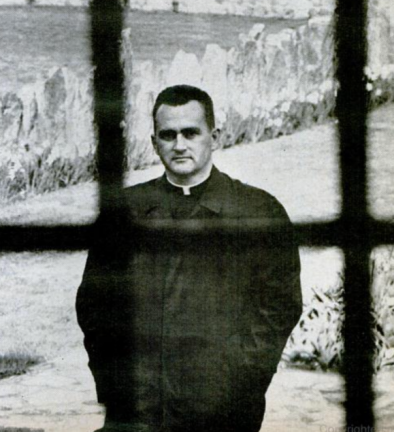

- Fr Philip Berrigan (brother of the similarly-active Fr Daniel Berrigan SJ), an opponent of US policy in Vietnam, and removed from teaching in a college seminary in New York to a slum parish in Baltimore. “His new diocesan superiors allow him full freedom to lecture on his views…” In Berrigan’s view the “‘Church as a community and a society has to begin to learn from the world.’” The profile, referring to Daniel in the first instance continues, “Like his brother, his deepest concern is that the Church and the priesthood take a more active and vital role in secular life. ‘The deeper we dig into the Bible and our history,’ he says, ‘the deeper we realize that God himself is a revolutionary reality, that he enters history in order to be the source and initiator of social and personal change.’”

- Fr Maurice Ouellet, a leader of the civil rights’ demonstrations in Selma, Alabama, was declared as “wild” about the issue by his bishop and removed to a seminary in Mystic, Connecticut. He states, “‘This whole new attitude in the Church is that there is not one man who stands at the the top, a medieval concept, the idea of a feudal lord with all the answers. The answer does not lie in allowing everyone to do as he sees fit. But we’re entering a new phase in which authority is something shared—not telling what to do so much as asking them what must be done.’ In his view, he continues ‘the work that Christ began, and that is to help men love one another.’”

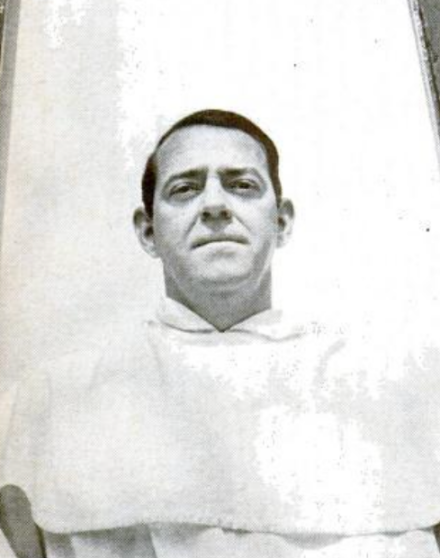

- Fr Clement Burns, a “Dominican intellectual, was removed from the faculty of LaSalle College in Philadelphia after being arrested in 1963 while leading a segregation protest in Cambridge, Maryland.” He was removed to a girls’ liberal arts college in Connecticut. His crusade centred on “the Catholic hierarchy…failing to respond to social causes” and its lack of democracy. Fr Burns is quoted: “‘St. Thomas said there can be no such thing as absolute obedience to a human being, that no one can order you to do something sinful. The other side of the coin is that there can be sins of omission. Sometimes when a superior says you cannot do that, to obey him would be a sin of omission. The role of the priest is to inspire his people, give them a vision, give them ambition for what they could do to bring about a better world. This generation of priests feels we are American and we’re going to be responsible and we are going to shape the institutions of this country like the Protestant ministers, Jewish rabbis and anybody else.’”

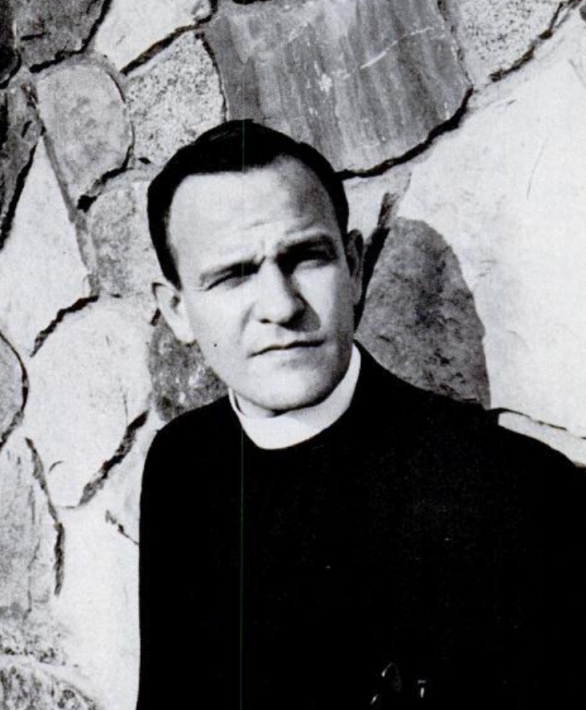

- Fr Gommar DePauw, “is a contrast to most of the other dissident priests. He is a conservative, leader of the Catholic Traditionalist Movement, which campaigns to preserve the traditional Latin Mass. He refers acidly to supporters of the new English Mass as ‘ecumaniacs’ with their ‘hootenanny liturgy.’ His superior ordered him to abandon his crusade ‘in terms that would have done credit to an Inquisition priest,’ and DePauw was removed from his teaching post at a Baltimore seminary. Now he lives in a rented room in New York.” Feeling uncomfortable initially at being labelled a rebel, “now I don’t mind as long as they let me explain what I’m rebelling against: the hypocrisy and abuse of authority, selling out our doctrine and trying to make it look as if the things we believed in all these years were erroneous…I am not fighting the decrees of Vatican II but the misinterpretation of those decrees. Catholics should have a choice between the new and the old masses. That’s exactly what we ask: a choice. This is the worst form of regimentation the Church has ever had. Whether you like the new liturgy or not you take it, they say. Well, Catholics have grown up. They don’t have to swallow this kind of kindergarten dictatorship any more, from the right or the left. We are more liberal than the unliberal liberals who say whether you like it or not you sing, you stand up, sit down, kneel, walk, smile, cry, dance. What is all this? Good old Pope John must be turning in his grave. He wanted more freedom. Look what we’re getting.’”

- Fr John De Witt shared Fr DePauw’s view of contemporary Church authority, but had a contrary view of liturgy. He removed from “his Negro parish in the Detroit slums for experimenting too freely with jazz and dance in the liturgy.” His punishment was to be moved an all-white parish, “which he calls ‘duller than hell. I’m trying to perform the classical function of loyal opposition in an institution in which the right to do this has not been recognized. Authority of the church? Control is what you mean…’” He continues, “‘Jesus never said “Be a Christian.” He said “live!” To live you’ve got to know where the action is, you’ve got to know who the phonies are, and you’ve got to know what risks to take, how society is put together. I think this priestly garb is a sign of being a member of a privileged class…I would like to see a postecclesiastical kind of church, with the demise of all external signs of honor and glory and prestigious trappings, as fast as possible. The primary job of the priest should be human communication. The liturgy of the church should be a celebration, a real blast.’”

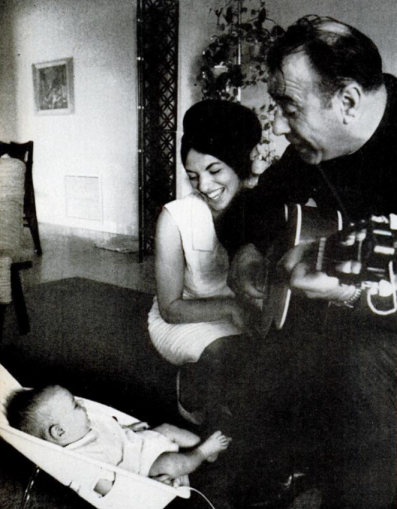

- Fr Anthony Girandola was the “most defiant of all these priests, the only one his fellow dissidents consider to be in open rebellion.” At the time of the article he had married and fathered a child, after “years of anguished efforts to maintain his vows, during which time his Church superiors sent him to a series of retreat houses for psychiatric treatment.” This brought automatic excommunication, “but Father Girandola has refused to give up his ministry. He now offers mass in a former Assembly of God church in St. Petersburg, Fla. His parishoners [sic] are a mixed group of Catholics and non-Catholics who are sympathetic to his cause.” His cause was clerical celibacy. “Most Catholics have the idea that celibacy always was. It wasn’t. The vow of celibacy is dispensable; the Church has the right and power to dispense with it and it does…It boils down to a matter of money with the Church. You pay a priest $100 a month. You can’t pay a married man that. As for my case, the important thing is that people are talking. I don’t care if they curse or damn me. I look to the Catholic people —we want the Church to at least talk about it. Unless we ask questions, unless we seek answers, we’re not helping the Church.’”

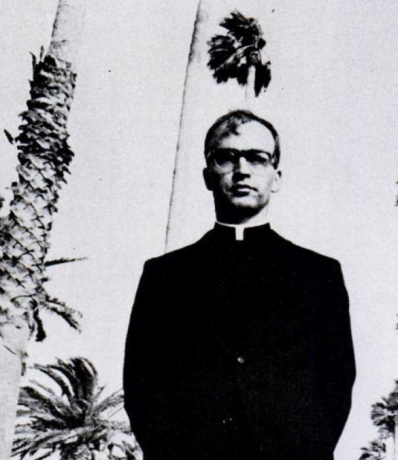

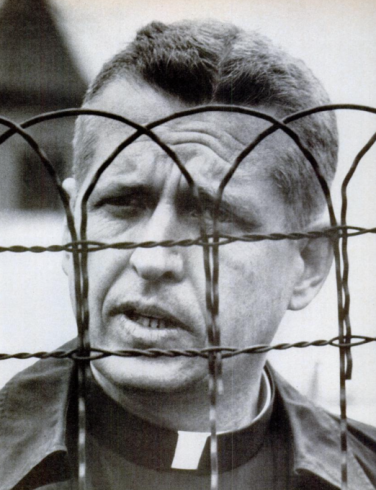

- Fr William DuBay, at 31, “has created a furor with his persistent criticism of the Church hierarchy, culminating in his call for priests to form a labor union.” Suspended and then working at a drug rehabilitation centre, he continued to focus outspokenly on the role of the bishops. ”‘Pope John sought to have the Church lend direction to all humanity, to have the Church be concerned outside itself. But the American bishops have failed to grasp the idea. Church reform will depend most of all on how well it brings itself back into the realm of ethics and ethical development. The Church must become aware of its own ethical standards. Is it democratic? Can it reach internal decisions in a reasonable, intelligent manner? Not the American church. We have a management church dominated by the hierarchy, with laymen and priests taking orders but never participating in the making of decisions. If priests are to deal with the hierarchy as equals, they must use their power effectively. They have the inherent power, but only through a union will they be able to achieve their rights. You go to the hierarchy for help, but they can’t help you because “it just isn’t done,” and they’ll show you the exact rule, underlined like a Baptist Bible. That’s why administration is so deadly, because you become more and more a function within a machine. To innovate means the administration has failed in the past so you don’t want to make them look bad.’”

Plus ça change! It is fascinating to hear what these agitating priests were promoting and rejecting. All of them are facing and adapting to a rapidly changing world, but are mostly adopting worldly principles to do so. This rather surrenders the ground before engagement has begun. For all of them, even Fr DePauw, the exercise of authority in the Church is a burning issue. Bishops are faulted for a sort of totalitarian and binary outlook on the Church in the midst of this world. Looking at the current fracas about synodality, it seems some issues today are a direct legacy of the 60s: episcopal ministry and democracy in the Church, clerical celibacy, and liturgy as centred on the congregation—“a blast”, to quote Fr DeWitt. None of these radical priests directly questions the role and authority of the papacy, at least not at this juncture.

What became of these men? (All their photos are taken from the Life article.)

Fr DuBay (above) was a little more radical than Life let on. He had been disciplined by Cardinal Macintyre of Los Angeles for his advocacy of desegregation while pastor at a white-segregated parish, and had petitioned Paul VI in 1964 to remove Macintyre as archbishop! Suspension finally came in early 1966 for his publication of The Human Church which urged a democratization of the Catholic Church. He married in 1968 and divorced in 1971, when he came out as homosexual and became a champion of the gay rights movement. He died earlier this year, aged 87. One wonders how much of his struggle with the Church was an externalization of his interior struggles.

Fr Girandola (above) became something of a celebrity after coming out as a married priest, and attracted media attention beyond Life. His 1968 memoir, The Most Defiant Priest, made the New York Times best-seller list and won the Mark Twain Award. He left Florida and settled finally in Maryland, where he became a lawyer. He would often wear his clerical collar and had contact with both Catholic and Episcopalian congregations. He never renounced his identity as a priest. He remained faithful to his wife and fathered two sons. He died in 1997, aged 72. Once again, one wonders whether Girandola was motivated more by his own inner turmoil, unconsciously projected on to a cause that offered the chimera of resolution to his struggles.

Finding information on Fr DeWitt (above) has been more difficult, as he seems to have lived out of the limelight. He left the active priesthood soon after the Life article, he was a professor at Wayne State University for 25 years, and later practised as a psychologist. He married in 1967, fathering a son, and remained with his wife until his death aged 89 in 2020, in Jacksonville, Florida where he had moved to be near his son. He seems to have had little involvement with the Church after his marriage.

Finding perhaps a celebrity not quite equal to that of the Berrigan brothers was Fr DePauw (above), who founded and remained active in the Catholic Traditionalist Movement. Belgian by birth, he was ordained a priest in Ghent during the Second World War, serving in the Belgian resistance. He arrived in the US in 1949 and would later serve as a peritus at the Council. Before the Council ended he was in conflict with Cardinal Shehan of Baltimore on the interpretation of conciliar decrees, not least regarding the liturgy. As a result he attempted to transfer his incardination from Baltimore to Tivoli in late 1965, without informing Shehan, which was contrary to canon law. Suspension soon followed. In 1968 he erected a chapel on Long Island, New York, where he ministered using the preconciliar liturgical books till his death in 2005, aged 86.

Fr Burns (above) persevered in the Dominican habit. Notoriety did not stop him continuing in college and university ministry. For 20 years, from 1974, he began an itinerant preaching ministry alongside other duties in his order, including serving as student master and a community prior in the 1980s. In 1994 he added parish ministry to his CV, while later serving as novice master in his Dominican province. He died in 2014, aged 86, in good standing with the Church and the Dominicans.

Fr Ouellet (above) was an Edmundite priest. He served in Selma, Alabama in the early 1950s before moving to New York and serving in senior roles for his congregation. On his return to Selma in 1961 he became active in civil rights, collaborating with Martin Luther King. He was transferred from Selma at the demand of Archbishop Toolen of Mobile, going to Mystic to be his congregation’s novice master, later training to be a psychologist. (In fairness to Toolen, he had desegregated his schools in 1964, and was thus derided as the “n*gger bishop;” his action against Ouellet resulted from the bishop’s attempt to walk a fine line between civil reform and keeping the peace.) He served in various colleges as a counsellor, and later would become a parish pastor. He retired to Florida in 1993, and then moved back to Selma in 2003. He died there in 2011, aged 84, in good standing with the Church, and was buried in Vermont.

Fr Philip Berrigan was a Josephite priest. Along with his Jesuit brother, he was a prominent activist for social justice and employed civil disobedience, especially in the cause of peace and nuclear disarmament. He was jailed several times, even before this article in Life, for a total of almost 11 years of imprisonment. In 1969 he contracted a clandestine marriage with a former nun, finally registering it in 1973, at which point both were excommunicated, though they were later reconciled with the Church. His activism is conveniently delineated by the names of the groups he was involved with: the Baltimore Four, the Catonsville Nine, the Harrisburg Seven, and the Plowshares Movement. He died in 2002, aged 79, and was given a Catholic burial.

One cannot but feel and appreciate their humanity as they battled their demons and followed their lights. Nevertheless, one is left with a strong sense that in some of them, the human urge often triumphed over the divine call, and that for all their principles, and though they contributed to some good social causes, they undermined the Church in the process. Maybe they are more symptoms than causes, but the underlying malady seems active still in the Church today. May they all rest in peace.

Next time, a different focus from Life in 1966.

[PS The system is refusing to accept my resizing of the photos, so if some seem much larger than they should, my apologies.]

PPS There were some letters to the editor a couple of weeks later, in the 15 July edition of Life. Interesting…

Very well done synopsis of the ecclesial mess of the 1960’s and beyond. Thank you!